This essay series examines best-in-class business and strategy models, and adapts them for use by creative enterprises. Check out the first essay for a short introduction, or dive right into the model below.

—

There are about a million sources out there explaining how to make a business model. There’s the business model canvas. The Lean canvas. The strategy sketch. All of these are great for mapping the outlines of your business, and figure out the basic financial viability of your model.

However, when your business is up and running, there’s a good chance you won’t return to this model unless you are contemplating a big pivot. After all, when business is good, the model must be working, right?

The next question then, which is one a business model like the ones above can’t answer as easily, is how do I ensure the sustained success of my business? And if there is, how can we model this?

Sustainable competitive advantage

According to Michael Porter, the key to sustained financial success is a unique strategy that puts you in a position of competitive advantage.

Strategy, to Porter, is the sum total of choices you are making as a company that allow you offer value that is distinct from your competition. Competing to be unique is highly preferable to competing to be the best. It allows you to play the game of business like a positive sum game, rather than a zero sum game. For creative companies, the question of what or who is “best” is often moot anyway.

Having a competitive advantage simply means that your strategy is allowing you to either operate at a lower cost, or command a higher price than your competition. It is a measure of the value you have created for customers, and how much of that value you are able to capture for yourself.

So how do you come up with a strategy that helps you do this? Porter has devised five tests that a good strategy must pass, that will help you define a unique strategy for your company. Every strategy requires:

- A distinctive value proposition

- A tailored value chain

- Tradeoffs different from rivals

- Fit across value chain

- Continuity over time

Let’s look at each of these in a bit more detail.

A distinctive value proposition

Your value proposition needs to answer three questions:

- Which customers are you going to serve?

- Which needs are you going to meet?

- What relative price will provice accaptable value for customers and accaptable profitability for the company?

If you can’t define a distinctive value proposition, you are competing with others to be the best, and you don’t want that.

A tailored value chain

A value chain is the set of activities you perform that together allows you to create and deliver your product or service. Your value chain should be tailored to your specific value proposition. If your value chain could just as easily deliver a completely different value proposition, you will have a very hard time succesfully differentiating yourself from the competition.

As you can see, the first two tests bring together the external perspective of the customer, and the internal perspective of company operations.

Tradeoffs different from rivals

The main thing about strategy, is that strategy requires choice.

This is most tangible in the concept of tradeoffs. Tradeoffs are the strategic equivalent to a fork in the road. You can pick one or the other, but not both. An simple example is the choice between high quality or low price. Choosing one allows for a myriad of possible strategies, but it is almost impossible to choose both and do well. Choosing what *not* to do is an essential part of the strategic process.

Fit across value chain

Fit describes that way in which the value or cost of one activity are affected by the way other activities are performed. It is a measure of internal consistency.

Porter identifies three basic types of fit:

- Basic consistency, when everything contributes to a central theme

- Synergy, when activities complement or reinforce each other

- Substitution, when performing one activity makes it possible to eliminate another.

The better the fit between your activities, the better the chance your strategy will pay off and lead to sustainable competitive advantage.

Continuity over time

As Joan Magretta puts it in Understanding Michael Porter, “Strategy isn’t a stir fry; it’s a stew”.

It takes time to hone in on a strategy that works best for you and your company. In the mean time, continuity ensures that you can build a reliable, recognizable brand, and enables you to develop and adapt capabilities and skills that are tailored to your strategy.

Leaving aside continuity, which is rather self-explanatory, the fourth test is where all of Porter’s concepts come together; literally. Your value proposition, value chain and tradeoffs should all fit together and form a coherent strategy. The better they fit, the better your chances of finding a position of sustainable competitive advantage.

Porter has helpfully devised a handy model, which he calls the activity system map, which you can use to map your company’s significant activities, their relationship to the value proposition, and each other.

The activity system map

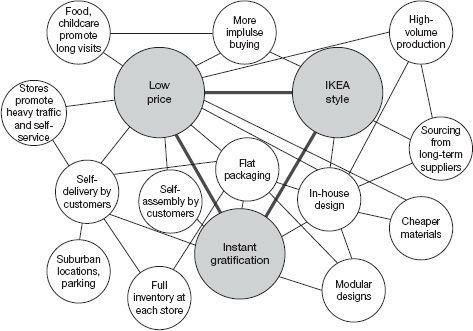

Let’s take a look at an example first. Here is the IKEA activity system map Joan Magretta shares in Understanding Michael Porter:

The larger, darker nodes in the represent the value proposition, or at least its most salient elements. Surrounding this are the various activities, value chain elements and specific tradeoffs that make this proposition possible. Moreover, the elements are linked where there is fit–where they support or enhance each other. The more closely the map is linked, the better the strategic fit, and the more difficult it will be for a competitor to reproduce your unique strategy.

As you can see, the model contains similar elements to those you’d find in one of the various business models outlined in the first paragraph of this essay. However, the focus on strategy and fit makes it much more useful in the later stages of your company, when you’re trying to fine-tune and future-proof the financial engine of your company.

Getting started

Here’s how you can create your own activity system map.

- First, list the three to five most imporant elements of your value proposition. Do this from the perspective of your customer. What are the elements that draw them to your product or service, and not those of a competitor? Be realistic, honest, and as specific as possible. Put these elements in the middle of your model.

- Next, list all of the activities performed by your company, all the elements in your value chain, and all the tradeoff decisions you’ve made. From this list, select those items that generate the most value for the customer or are most important for delevering that value, and those that generate significant cost. Add these to the map.

- Now, link the items wherever they enhance or support each other, wherever there is fit.

The resulting map can be a great help in identifying strong and weak areas in your strategy. Ask yourself how you can improve what you see: Are there elements that could be linked to more items than they are right now, increasing overall fit? Are there any items missing that, when added, would improve overall fit?

Everything you come up in this step can be used as a starting point for improving that part of your business, bringing it more in line with your overall strategy and bringing you one step closer to having a sustainable competitive advantage.

Bonus step

Depending on where you are as a company (and how much you liked making the first map) it can be worth going one step further, and imagining an activity system map for the ideal version of your company. Instead of looking at where you are and what next steps can be, you will be inverting and working backwards from an imagined, ideal state.

First, think of where you want to end up. For what reasons should your customers flock to your product or solutions? What elements should your value proposition contain to support that ideal?

Next, think of the various elements that you would need to make that improved value proposition a reality. What activities would you need to perform? What would your value chain need to look like? What tradeoffs would you have to make?

Finally, link the items as you have for your first activity system map.

Depending on your situation and your ambitions, the two resulting maps may be quite similar, or vastly different. In either case, the gaps between both models can inform the steps you need to take to close the distance between your current and ideal state.

I hope you’ll give making your own map a shot. If you do, I’d love to see the results, and hear about the insights they did or didn’t provide.

If you made it this far, consider subscribing to my newsletter. You’ll be the first to hear about new essays!

Photo by Sam Moqadam on Unsplash